By Charlie Buterbaugh | March 15, 2022

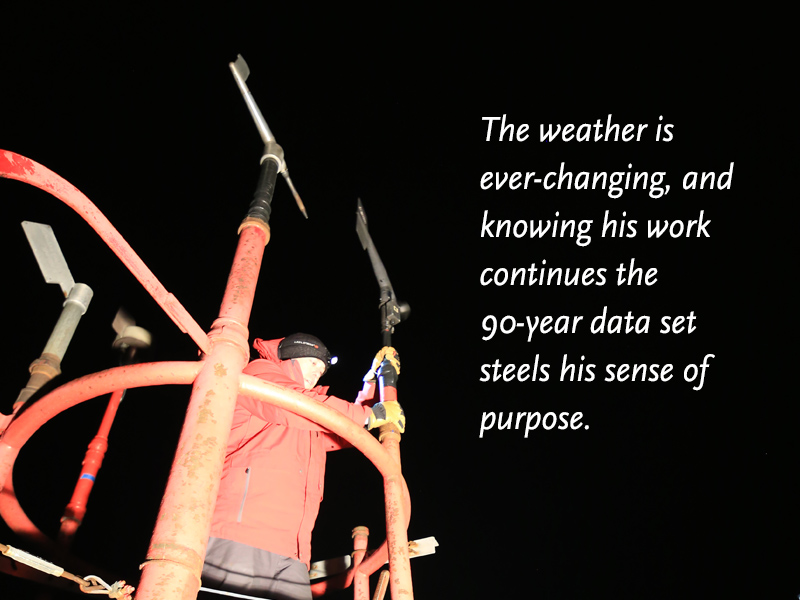

Staff Meteorologist Ryan Knapp sets an anemometer on the observation tower.

Well over a mile above the valley of Mount Washington, in a weather station built into boulders deposited tens of thousands of years ago, a night observer keeps track of data through the night, maintaining one of North America’s longest continuous alpine climate records.

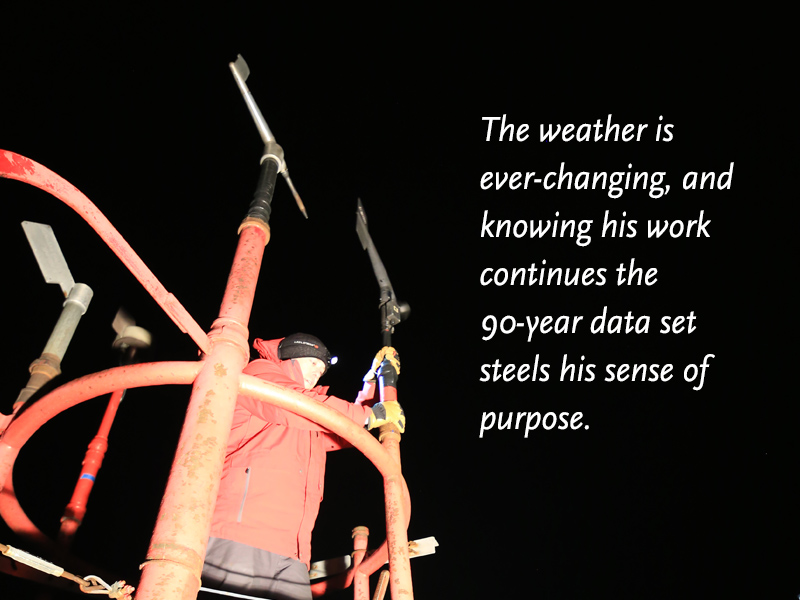

He is mainly focused on the minutes, completing observations between 00:49 and 00:59 past every hour. Routine and process rule the night, but no two nights make the same weather. The consistency of process, timing, and location assure continuation of a 90-year data set. Weather presents a far less reliable dimension, especially on Mount Washington, where cycles are shaped by cold fronts, warm fronts, and extreme conditions that arrive as they please.

It’s 5:30 p.m. on a mid-November Tuesday evening, and Staff Meteorologist Ryan Knapp seems accustomed to darkness, keeping the weather room dimly lit. He relieves the two day observers whose work started 12 hours ago. The transition between staff is critical. They compare notes about current conditions and forward-looking models.

“If you don’t write something down, it could quickly become too little too late,” says Knapp. “Weather systems could be arriving hours ahead of what the models are saying.”

His running analysis combines real-time observations at the summit with data charts and weather maps displayed on multiple screens. Tonight, a low-pressure system approaching from the northwest pushes dry air like a bulldozer, creating pockets between moist layers.

The meteorologist checks data quality, verifying figures entered during the prior day to keep a clean baseline. In addition to the nightly checks, the team circles back to assure quality each morning, then again every five days, and once more at the end of the month.

“That’s what goes into our 90-year record,” says Knapp, referring to the monthly review.

Before the next ob, we head downstairs for dinner in the crew’s living quarters. Seated at a long table, eating sautéed vegetables and pizzas charred by a commercial gas range, the three meteorologists and one intern debate whether the approaching cold front will bring freezing rain, sleet, or snow. Nimbus, the observatory’s gray shorthair cat named after clouds that bring precipitation, makes his presence known.

After dinner, the crew scrubs and vacuums the entire quarters, including kitchen, pantry, bathroom, bunk rooms, and living room. They’re tired but in high spirits. Snow is in the forecast. And their off week starts tomorrow after they welcome the alternating crew of observers and travel down the mountain, this time of year by pickup truck on the auto road. If the snow is deep, they’ll stop to put chains on the tires. In the back of their minds, they know the whole trip could be delayed by dense fog or high winds above tree line.

Knapp’s short dinner break ends and he heads back up to the weather room. Except for my questions, he is alone once again for a nocturnal routine he has kept for 16 years.

Just after 7:45, he gears up briskly and ascends the observation tower, opens the door beneath an A-frame protecting against chunks of rime that fly when winds accelerate, and steps onto the vast observation deck, walking in darkness to the north end. He counts two layers of clouds below and three aloft.

The meteorologist heads to the designated spot for measuring ambient air temperature, turns his headlamp on, and spins the sling psychrometer, a low-tech instrument that’s reliable in a variety of extreme conditions. This manual weather observation process has been happening the same way, every hour, since 1932. With side-by-side dry-bulb and wet-bulb thermometers, measurements are used to calculate dew point and relative humidity, the amount of water vapor in the air.

During the next ob, he climbs three flights of stairs and ladders to the top of the observation tower, perched in darkness above anywhere attached to earth in the northeastern U.S. He checks the heated anemometers and, if needed, removes ice that accumulates fast as winds accelerate and temperatures plummet. Tonight, it’s only hovering around freezing with winds gusting at 50 mph.

Heading inside, he closes the hatch at the top of the tower, quieting the west winds blowing out of the chasm of the Ammonoosuc Ravine against Mount Washington’s windward flank, and again returns to the weather room to log data, check radar, and perform other tasks until he heads outside again regardless of the weather, repeating this routine through the night.

Asked if the work ever gets monotonous, he says no. The weather is ever-changing, and knowing his work continues the 90-year data set steels his sense of purpose.

“It’s almost like having the mountain to myself,” he says. “I only have to worry about the weather.”

Data is inputted after every hourly observation through the night.

A playlist and mug of coffee also keep him going. He responds to a question on MWOBS’ Facebook page about yesterday’s photo of a cap cloud that formed over the summit. Knapp doubles as the observatory’s photo administrator, and his summit photography has attracted a colossal following.

He’s known at the summit for rating sunrises on a scale of one to ten. A three on his scale is likely an eight or nine on ours.

But from now until early March, he’ll go to sleep before sunrise, missing the morning blue hour.

It’s approaching 1:00 a.m. and the meteorologist starts a synoptic observation, a six-hour detailed snapshot of conditions. He records maximum and minimum temperature, atmospheric pressure tendency, and precipitation types and totals. This all gets delivered to the National Weather Service. Being prompt matters. The synoptic data feeds weather models that Mount Washington’s observers and many other meteorologists rely on for accurate forecasting.

The complexity of his work increases after the 1:00 synoptic. He starts to work on the daily mountain forecasts between 2:00 and 3:00, staying keenly aware of the observatory’s backcountry audience. The

Mount Washington and

Higher Summits forecasts need to be posted on mountwashington.org before 5:00 a.m. The weather is always changing and the stakes are high. Search and rescue teams, climbing guides, and others rely on MWOBS’ forecasting accuracy, helping them decide when to head out, how to modify plans, or to postpone.

After a few hours of sleep in one of the cozy wood-paneled bunk rooms, I head back to the weather room and overhear Knapp recording his voice for the audio forecast. Falling snow is starting to accumulate at 5:15 when Weather Observer Sam Robinson arrives in the weather room to start his day. He fields a round of probing, collegial questions from Knapp about data points entered the previous day. It’s all part of keeping the record straight.

Knapp and Robinson stay composed as ever. With winds on the increase and a snow storm in process, care will be needed on this shift change day as the next crew makes their way to the alpine zone for another challenging week at the weather station.

Knapp reads in an observatory bunk room after completing his nightly shift.

If you value our work,

consider a donation to Mount Washington Observatory, a private, nonprofit institution. Donations directly support the continuation of forecasting, climate data, and educational work at the summit of Mount Washington. Any donation qualifies you as a member. $5 per month gives you a one-year subscription to

Windswept, our member magazine where this story was originally published.

About the Author

Charlie Buterbaugh is the Director of Communications at Mount Washington Observatory.