Extreme Commuting on Mount Washington

By Lauren Clem | Winter 2024/2025

This article was originally published in the Winter 2024/25 edition of Mt Washington Valley Vibe, a unique, outdoor-focused, seasonally-printed publication in the Mt. Washington Valley of New Hampshire.

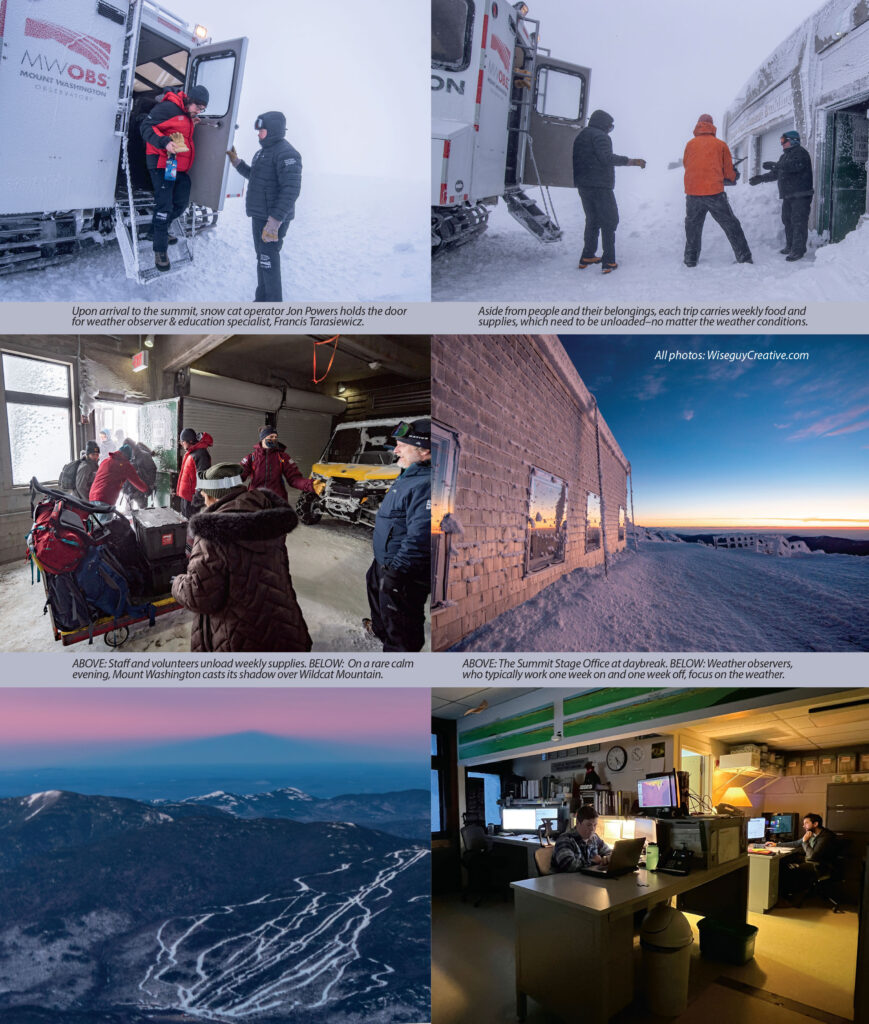

WiseguyCreative.com photo

In his 19 years serving as a weather observer for the Mount Washington Observatory, Ryan Knapp has seen it all.

He’s seen 10-foot snow drifts piled against the walls of the Sherman Adams Building. He’s experienced minus-40-degree temperatures with a wind chill of 101 below. He’s seen clear days with a view 130 miles in every direction, and starry nights when the aurora borealis danced above the Presidential Range.

“No two days are exactly the same,” says Knapp, who currently works the overnight shift at the summit observatory. “What’s nice about this job is you do the forecast in the morning, you wake up in the evening, and you’re out there experiencing what you forecasted for.”

Still, some days are more memorable than others. Knapp remembers clearly the night of February 24, 2019, when the wind reached speeds of 171 miles per hour—a monthly record for the Observatory, and his personal wind speed record during his years on the summit.

“We sat down for dinner, and you could hear every wind that was occurring,” he says. “We have a little monitor downstairs near our dining table, and every time we heard a wind gust, we’d look at the monitor.”

But it’s what happened over the following days that cemented the event in Knapp’s memory. The Observatory, a nonprofit organization that relies on donations and grants, offers overnight EduTrips to members of the public. Guests typically head up the mountain by snow cat on Mondays and leave the following day. On this week, however, the persistent high winds combined with nearly a foot of snow stranded the group on the summit, and they were forced to spend an extra night. Knapp says there were no complaints from guests, who’d been warned they may get to witness “the world’s worst weather” firsthand.

“The next two days we had 123 miles per hour on the 26th– and on the 27th, we had 103-mile-per-hour winds,” he says. “Not very many people get to experience those kinds of winds, but more importantly, survive those kinds of winds.”

After aborting its mission on Tuesday, the Observatory snow cat was eventually able to retrieve the guests—and bring a fresh shift of weather observers—on Wednesday. Scaling a 6,288-foot mountain in winter is never easy, but Knapp explains how it can be particularly treacherous in high winds. As the snow cat heads up the Mt. Washington Auto Road, the treads kick up snow, obscuring visibility as the wind piles snow drifts in its path. A single trip can take hours, and the arrival must be timed exactly right.

“All that snow was continuing to pile onto the road, so it required a lot of blading to continue to get up to the summit,” Knapp recalls.

In extreme weather, as well as everyday conditions, Observatory staff rely on a team of snow cat operators to get them to and from the summit safely. The snow cat (often referred to as a Sno-Cat after its trademarked variety) offers a way to reach the summit in potentially deadly winter conditions, but the job requires a level of skill and judgment far beyond that of the typical weather enthusiast. Without these specialized operators, the more than century-old tradition of weather observing from the summit—and the forecasts it produces for all in the Mt. Washington Valley—would quickly evaporate.

Scaling the Mountain

The 30-foot birch poles stand up beside the Auto Road like the pylons of an unfinished chairlift. Here in the alpine zone, they tower over everything around us, marking the way to the summit in all weather conditions—or at least, that’s the idea.

“There have been years that the tops of those have been completely covered,” says Jon Powers, transportation coordinator for the Mount Washington Observatory.

Powers, behind the wheel of the Observatory’s white pickup truck, has offered to show me how staff make the trip to the summit in the unpredictable winter and shoulder seasons. As luck would have it, the White Mountains have delivered an unseasonably warm November day, and tourists zoom by on their way up the Auto Road. On this mountain, you can never be too prepared, and halfway up the road, the Observatory’s white Bombardier snow cat sits parked at an overlook, lying in wait for colder temperatures. At the first sign of reliable snow, operators will trade their tires for treads and fire up the snow cat.

Operating a snow cat is far more than just driving over snow. The machine’s blade is made for leveling and shaping snow rather than clearing it, allowing operators to widen the road as they go. Underneath the treads, 196 carbide picks provide traction, keeping the occupants from falling into a treacherous slide. The greatest challenge, Powers says, is visibility. With the mountain’s high winds and constant drifts, the landscape is never static, and operators are often navigating through poor visibility on a path that shifts by the hour.

“Say on Wednesday you went up on shift change and made the road perfectly clean,” he says. “If there’s a snowstorm overnight and you get enough snow and the right winds, there’s no road anymore, so you have to rebuild the whole thing.”

Powers—who works as a captain and paramedic for the Conway Fire Department when he’s not on the Auto Road—oversees a team of three operators in charge of getting people and supplies up and down the mountain. In the winter, the snow cat operates as many as five days a week. This includes weekly shift changes, EduTrips, media trips, and other opportunities to get the word out about the Observatory’s work.

On a good day, traveling at a max speed of 8 miles an hour, the snow cat can reach the summit in about 90 minutes. More often, the trip lasts several hours. Powers recalls one EduTrip last year when the journey took seven and a half hours. In the worst conditions, the snow cat turns around before reaching the summit. It’s a call made by the operator, he says, one that can distinguish an inexperienced driver from a good one.

“What you can see is what you drive. If you can’t see, you turn around,” he says.

Even during shoulder season, the changing temperatures present challenges. The tractor’s carbide picks damage the road’s asphalt surface, so staff transport the tractor via flatbed truck to a staging point midway up the mountain early in the season. When snow begins to fall at higher elevations, staff members drive the bare portion of the road in a pickup or van—sometimes using tire chains—then transfer to the snow cat to complete the journey. The whole routine can sometimes take longer than a snow cat trip from base to summit.

The worsening of extreme weather studied by scientists at the summit can also hinder their ability to reach it. According to Charlie Buterbaugh, director of external affairs for the Observatory, summit researchers have identified an increased incidence of rain-on-snow events, affecting snowpack stability and avalanche risk, as well as transportation. In spring 2023, heavy rains washed out portions of the Auto Road and shut it down for a week, forcing staff members to instead rely on the Mount Washington Cog Railway to provide transportation for shift changes.

“With the increase of extreme weather throughout the country, the Observatory is more and more being seen as kind of a hub for learning and research on understanding extreme weather,” Buterbaugh says.

Summit Life

As we round the summit, a white cross near the top of the Cog Railway reminds us that despite the mild weather, visitors to the mountain are never far from danger. The Sherman Adams Building is closed for the season, with gift shop merchandise and maintenance supplies stacked around its silent halls. Inside a door to the Observatory, Karl Philippoff and Francis Tarasiewicz record their hourly measurements in the weather room while Knapp rests for his overnight shift. Weather observers work one week on and one week off, traveling up to the summit on Wednesdays. They’re typically accompanied by one or two interns and several volunteers, who handle the cooking and cleaning in exchange for a chance to stay on the summit overnight.

On the day I visit, a crockpot of chili is bubbling on the counter, and Nimbus the resident summit cat is hiding away in a corner, fast asleep. Philippoff, a native of New Jersey, describes his coworkers as his “summit family” and notes he spends as much time on the summit as away. Even for a weather enthusiast, though, the hours are long, and all three observers recall with annoyance days when extreme weather delayed their shift change.

“I love being up here, but eight days is still a long time. Usually, I’m pretty ready to go down,” Philippoff says.

For Knapp and Tarasiewicz, the ride up is one of the less enjoyable parts of the job. Knapp experiences motion sickness and prefers to walk behind the snow cat when conditions allow. Tarasiewicz, meanwhile, is afraid of heights, and more than two years in, still sits on the left side of the tractor cab, facing the mountain, on the way up.

“I always liken the trip in the snow cat to the teacup ride at Disneyland on a boat,” Knapp says.

“If you’re prone to motion sickness, Dramamine is your best friend.”

Aside from people, the snow cat carries weekly supplies and occasional odds and ends—like a Christmas tree in December, and Nimbus when he has a vet appointment in the Valley. The Observatory is stocked with several weeks’ worth of food, and a generator serves the building in times of power outage. (The summit is connected to the electrical grid via the Cog Railway side.)

Despite the supplies, observers are aware that in many ways, they’re just as isolated as hikers. The summit has a helipad, but landings are not always possible, and any trip to the base depends on weather conditions and an operator’s ability to travel the 7-and-a-half miles to reach it. Last February, Philippoff, and Tarasiewicz were on the mountain for a cold snap when the Observatory tied its record low temperature of -47 degrees—conditions that would quickly turn fatal outside the Observatory doors.

“A lot of people have the misconception that we’re so close to civilization that someone’s just going to come and rescue us,” Knapp observes. “Just because there’s a road going up it, doesn’t mean the cavalry’s going to come save you.”

WiseguyCreative.com photo

History of Transport

Despite the long history of weather observing on the mountain going back to the first private expedition in 1870, snow cats are a relatively new technology on Mount Washington. The Observatory didn’t purchase its first snow cat until 1979. That first tractor came to the mountain from Cranmore, where it had been used to groom ski trails.

In the early days, observers hiked up the mountain along the Cog Railway tracks, according to Peter Crane, curator of the Observatory’s Gladys Brooks Memorial Library. Until the completion of Fabyan Station in the 1870s, observers arrived at the base in a sleigh from Littleton stocked with supplies. Later observers would hike up via the Auto Road on the eastern side.

“The typical routine was to get material up the mountain in the fall for the winter,” Crane says. “Any other material you were going to bring up over the course of the winter, you’d either hike up or ski up with it.”

By the 1950s, other entities—including military contractors and WMTW—had established their own snow cat routes on the mountain, and observers were able to hitch a ride. In the 60s or 70s, Crane says, the Observatory briefly experimented with snowmobiles, but the consensus was they were not well suited for summiting.

Since 1979, the Observatory has owned a series of four snow cats, with the current one more than two decades old. The Observatory has already secured $400,000 in congressional-directed funds to purchase a new PistenBully—the same brand owned by Mount Washington State Park and the Auto Road—to replace the white Bombardier, and hopes to have it on the mountain later this year.

With government and research entities depending on the Observatory’s daily weather observations, not to mention the thousands who read the Higher Summits Forecast every week, securing access to the summit is an essential role in the organization’s work. For operators like Powers—who says he prefers days that “make you use your brain a little bit”—the challenge of getting there safely is part of the appeal of the job. Even those less keen on the road traveled agree the destination makes it worth every bit.

“I just haven’t found anything that has that Venn diagram of what Mount Washington has to offer,” Knapp says.

Geologist Climbs Rock Pile, Looks Up

Geologist Climbs Rock Pile, Looks Up By Bailey Nordin Hello from the summit of Mount Washington! My name is Bailey Nordin, and I am the newest Weather Observer and Education Specialist joining the team

Life on Top of New England

Life on Top of New England By Anna Trujillo Hi everyone! My name is Anna Trujillo and I am one of the interns for the MWOBS winter season. I am super excited for the

I Haven’t Seen a Tree in 12 Days

I Haven’t Seen a Tree in 12 Days By Ryan Steinke A photo of me hiking Cathedral Ledge during my first off week. Hi everyone, my name is Ryan Steinke, and I