Weather 101: Tropical Storms

By Nicole Tallman, Past Weather Observer & Education Specialist | November 15, 2021

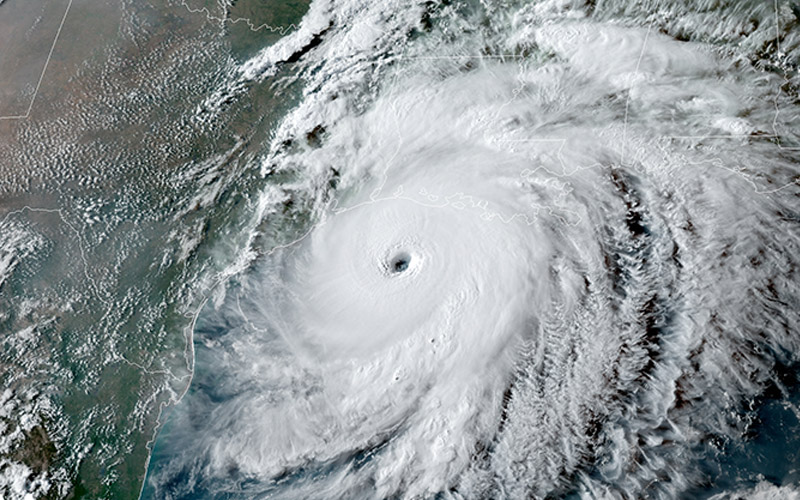

An example of a hurricane’s eye and surrounding eye wall, where the most ferocious winds of the storm occur. NOAA photo.

Come late summer and early fall, we begin to hear more about activity in the tropics. The threat of hurricanes becomes more prominent and you may find yourself thinking about how and why these storms are forming.

One of the strongest storms known to people, a hurricane begins its life cycle as a cluster of thunderstorms in the tropical or sub-tropical waters. These waters tend to be their warmest in the late summer after intense summer sunlight has been beating down for several months. The air surrounding the surface of the water begins to heat up, evaporating some of the moisture from the ocean. This is the initial ingredient needed to begin building a thunderstorm.

Once the air is warm and moist, it begins to rise through the cooler atmosphere. The ideal set up for developing strong storms is when the atmosphere is cool, yet the ocean waters are still warm. Moving into early fall, the oceans hold on to their warmth and the air begins to cool, creating “instability” for the warm moist air at the surface of the ocean. The air continues to rise in the atmosphere, creating a thunderstorm.

The ocean continues to warm the air closest to the water’s surface and in turn, feeds the rising pocket of air. This allows for low-pressure to form because the air is rising up higher into the atmosphere. Low-pressure centers in the Northern Hemisphere rotate counterclockwise, and in the development of a hurricane, you will start to see the cluster of thunderstorms become more organized and even begin to rotate.

Once the system has its own cut-off low-pressure system, winds will begin to increase, creating a stronger storm. Once winds reach 39 mph the storm gets the label of a tropical storm, and they become a hurricane at 74 mph.

The categories of a hurricane on the Saffir Simpson scale are wind-dependent, and as the storm produces higher and higher winds, it can increase itself to a category 5 hurricane, the strongest storm known. A very indicative physical feature of a strong hurricane is its eye. This is the calm center of the low-pressure system where winds die down and rain ceases. However, surrounding the eye is the eye wall, which has the most ferocious winds of the storm. Very strong hurricanes will develop this eye, which can clearly be visible from satellite, like in the example below.

A few hazards of hurricanes include the devastating wind speeds, storms surge, very strong thunderstorms and even tornadoes imbedded in the rain bands of the hurricane.

Most of these hazards dwindle once a hurricane makes landfall and is no longer over its main energy source, the warm ocean waters. However, hurricanes that have weakened or died out can continue to impact the weather of surrounding areas and areas “downstream” from the storm.

The immense amount of moisture and energy from hurricanes have been known to make their way from areas such as the gulf or southern east coast of the U.S. all the way to the Northeast. While it is less common for areas in New England to receive a direct impact of a hurricane, we quite frequently will get saturating rains, elevated winds, or a round of very inclement weather due to the remnants of tropical storms and hurricanes.

One recent example is Hurricane Isaias, which occurred in August 2020. Isaias made landfall on the coast of North Carolina with wind speeds sustained near 85 mph. It caused significant storm surge, and multiple tornadoes at landfall. Once on land, the storm weakened to a tropical storm and continued to impact cities such as New York and Philadelphia.

Remnants eventually made their way all the way north to the summit of Mount Washington, where the crew experienced heavy downpours and a max gust wind speed of 147 mph, a new record wind speed for the month of August.

In his blog dated August 5, 2020, Weather Observer Sam Robinson wrote, “Suddenly at 8PM sharp, the chart spiked showing a gust of 147 mph! The wind database was cross referenced and sure enough, it showed a peak gust of 146.7 mph from the southeast! Our crew celebrated the feat as it set all of our personal records and we then shared the news with the state park crew who also had a few new personal records set. We soon discovered that besides personal records, it also set a new all-time wind record for the month of August! The previous record was 142 mph set back in August of 1954.”

Massive and intense, tropical storms can impact areas all the way from their development to far past their site of landfall.

Team Flags Return for Seek the Peak’s 25th Anniversary

Team Flags Return for Seek the Peak's 25th Anniversary By MWOBS Staff Mount Washington Observatory is looking forward to continuing a much-loved tradition for Seek the Peak’s 25th Anniversary: Team flags. In inviting teams

Meet Summer Interns Zakiya, Max and Maddie

Meet Summer Interns Zakiya, Max and Maddie By MWOBS Staff We are excited to welcome six teammates to the summit of Mount Washington this summer! During their internship, these students and graduates will play

Saying Goodbye to the Summit

Saying Goodbye to the Summit By Alexis George After an extraordinary last three years working as a Weather Observer and Meteorologist, I am excited to pursue a different career. As sad I as am