Weather’s Influence on Wildfire Smoke in early June

Wildfires, smoke, and poor air quality have primarily been reserved for the West Coast. We’ve all seen the horrific videos from California’s destructive wildfires, but until recently these fires seemed like a distant threat. Then large portions of Quebec’s boreal forests began to burn. Millions across the eastern seaboard woke up on the morning of June 8 to a sunrise shrouded in smoke, and in New York City, hazardous air-quality captured national attention.

EarthCam view of smoke in New York City on the afternoon of June 8th

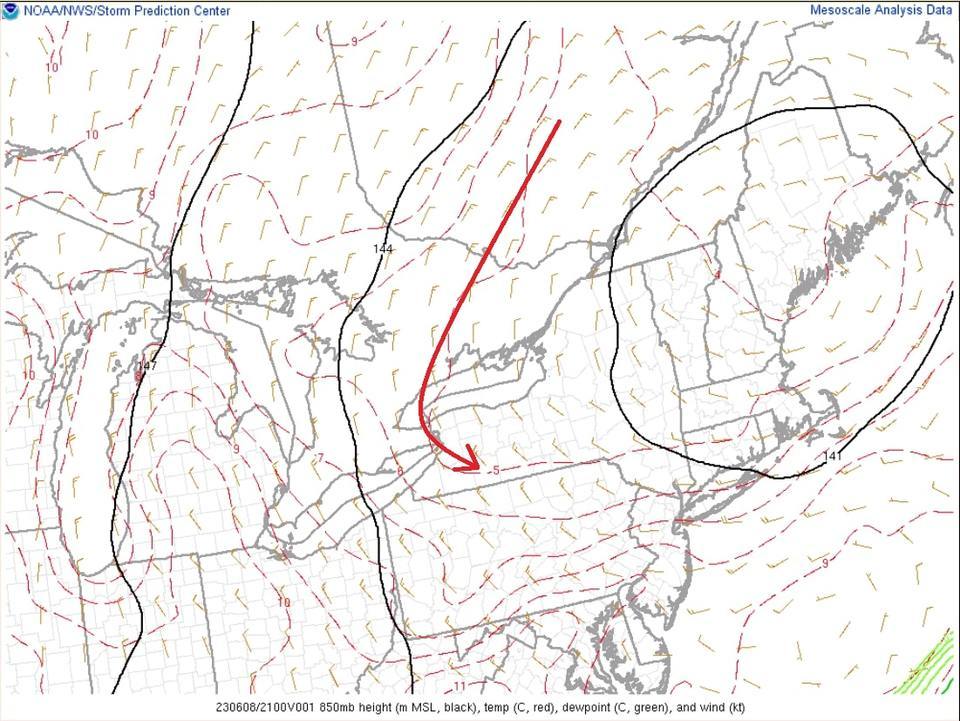

Out of sheer luck, the higher summits and thousands of hikers and adventurers in the White Mountains missed the brunt of the smoke that day, with most of it going well to the southwest. As the smoke has largely cleared, many are asking why this event happened? Can this happen again? And how can we stay safe during what is likely going to be a very smoky summer.

The weather configuration that set the stage for apocalyptic skies and poor air quality started up across Canada. Typically, after the harsh Arctic winter, a gradual snowmelt keeps the vast stretches of Boreal forest wet as the northern hemisphere transitions to summer. For the last few months, Canada has experienced exceptionally warm and dry conditions. This combination worked to quickly melt the winter’s snow and dry the forests and underbrush. All that was needed was a trigger, or in this case, thousands of triggers.

The ignition sources came from many natural and human causes. For parts of Canada, the start of the spring and summer season meant dry thunderstorms – packed with lightning but lacking rainfall. In many instances, these lightning storms ignited forests in far northern areas that are hundreds of miles away from adequate fire control resources. In other rural areas, seasonal brush burning combined with unseasonable dryness to bring fast-spreading brush fires, which became out-of-control wildfires.

The number of hectares burned so far this year in Canada

2023 has seen an incredible amount of acreage burned with some 13.3 million acres consumed by fire. In addition to the obvious natural impacts, these wildland fires have had a range of impacts on the people who live nearby and many others who respond to them. A record fire year has translated into a record level of mobilization.

At times, 20 separate agencies have been called to respond to the fires with weekly estimates of over 2,000 firefighters. These numbers may not seem impressive at first, but considering the average year sees less than five agencies and around 500 total wildland firefighters mobilized at the peak of fire season, this year has been unprecedented, and even more impressive in the fact that fire season doesn’t peak until July and August.

The human toll of wildfires is not limited only to those who see the flames. Smoke from these infernos spreads fire impacts to the farthest corners of the world, and into the heart of some of the most iconic cities. According to the EPA, smoke can result in a host of health issues ranging from phlegm, coughing, and wheezing all the way up to stroke and death for those with preexisting conditions like asthma and heart disease.

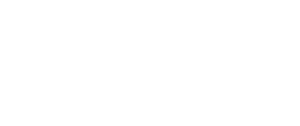

More recently, on the afternoon of June 8, areas of the Northeast experienced a significant wildfire smoke event that darkened the skies and sent air-quality into hazardous levels. New York and other major east coast cities that have long since solved their chronic air quality issues saw air quality index (AQI) values jump into the hazardous 300-400 range for multiple days. This smoke plume originated in Quebec and a complex weather pattern guided it southward.

Color-coded map of Air Quality Index (AQI) numbers on June 8th

Now that the event has come and gone, the question is naturally, can it happen again? In short, it absolutely can. Very few fundamentals have changed since the outbreak of smoky air. Most of Canada is still smoke-filled, and while areas in Alberta have seen some relief in the form of new rain and snow, fresh fires have begun in parts of Manitoba and Quebec.

The only factor in our favor at the moment is the track of low pressures. For now, most of the upper-level lows are pulling in air from the east, which is far from many of the source regions. All it would take would be a stronger low that pulled in air from the north.

With a dry and smoky summer ahead for Canada, what are some steps you can take for when the air becomes dangerous? The most important step is to limit your time outdoors, especially if you have preexisting conditions like heart or lung disease. Children and older individuals have higher risks from air pollution. On really bad air quality days, those risks spill over into healthier population groups. If you must go outside on a hazardous air quality day, a well fitted N-95 mask works quite well at keeping most of the particulate matter out. It can also help to better seal your windows and doors and to check your home’s air filters before smoke is expected to arrive.

Francis Tarasiewicz, Weather Observer & Education Specialist

Going with the Flow: Why New England Didn’t Experience Any Classic Nor’easters This Winter

Going with the Flow: Why New England Didn’t Experience Any Classic Nor’easters This Winter By Peter Edwards Why didn’t the Northeast experience any major snowstorms this year? If I had to guess, it’s the

A Look at The Big Wind and Measuring Extreme Winds At Mount Washington

A Look at The Big Wind and Measuring Extreme Winds at Mount Washington By Alexis George Ninety-one years ago on April 12th, Mount Washington Observatory recorded a world-record wind speed of 231 mph. While

MWOBS Weather Forecasts Expand Beyond the Higher Summits

MWOBS Weather Forecasts Expand Beyond the Higher Summits By Alex Branton One of the most utilized products provided by Mount Washington Observatory is the Higher Summits Forecast. This 48-hour forecast is written by MWOBS